The cult film icon and his cinematographer explain the unique process behind their bold new film and share timeless advice for artists of all stripes.

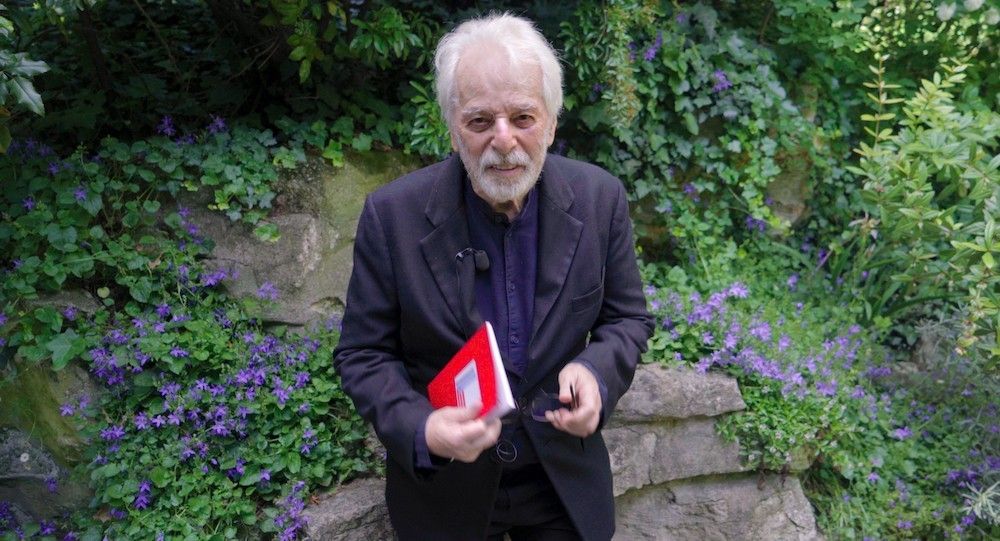

Alejandro Jodorowsky has spent his entire career as a searcher—searching for things he hasn’t yet tried or for things that never before existed.

That spirit of ingenuity is what led him, some 50 years ago, to create a form of artistic therapy he calls “Psychomagic.”

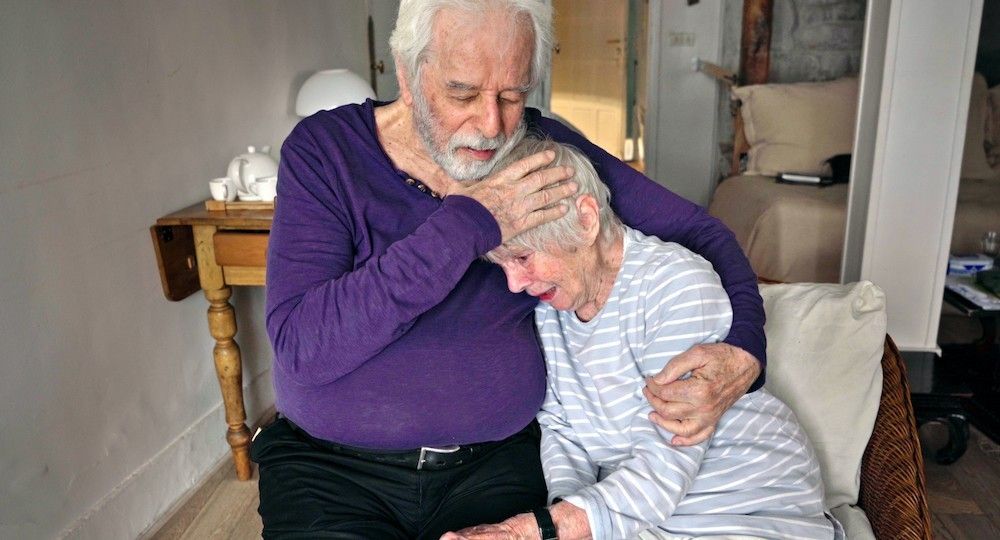

Psychomagic is tricky to explain to the uninitiated, but the basic concept is this: Jodorowsky meets with anyone suffering from psychological distress, takes some time to better understand that person’s genealogical roots, and then assigns an artistic “act” for them to perform in order to heal their psychic wounds.

These “acts” are the key ingredients of Jodorowsky’s latest film, Psychomagic: A Healing Art—an avant-garde documentary he made with his wife and cinematographer Pascale Montandon-Jodorowsky.

Over the course of the film, a number of people wrestling with inner-demons seek Jodorowsky’s help and the results are both bizarre and moving: A man with suicidal thoughts heads out to a desert to simulate the experience of being dead and buried; a woman with survivor’s guilt in the wake of her fiancé’s death goes skydiving; a man who wants to overcome a stutter paints himself gold and walks half-naked through the streets.

Jodorowsky readily admits that the benefits of Psychomagic are a “placebo,” and makes clear to both believers and skeptics of his methods that his intent is to not provide people with a miracle cure for their problems, but with an experience.

He and Montandon-Jodorowsky view Psychomagic: A Healing Art in much the same way: as a public service, rather than a way to turn a profit. To that end, they made the film on an entirely self-funded and crowdfunded budget and the production was stripped down to the extreme—no lights, no sets, no script, and no more than one camera.

We spoke with Jodorowsky and Montandon-Jodorowsky about their ambitious experiment, their unusual approach to filmmaking, and why they view cinema as a healing art—not a business.

NFS: Alejandro’s practice of Psychomagic, as well as the book that he published on the subject, have existed for many years before this film project began. What is it that led both of you to adapt this practice into a feature?

Jodorowsky: It’s a natural continuation of something. When I make art, I don't work intellectually or make plans. I just start and these things come naturally, and the concept of Psychomagic came like that. I started my career in improvisational theater—I made 100 theatrical plays in Mexico—and then I helped create the Panic movement. The difference, here, was that I was working in theater but also working with psychoanalysis. In psychoanalysis, you're working with words, but in Psychomagic you’re working with art.

Psychoanalysis is a science, Psychomagic is an art. But my initial goal was to heal psychological problems within myself. We are not doctors, and Psychomagic is not an industry that asks you to pay a lot of money to heal yourself. I do this for free... I devote my life to it without treating it as a business. It comes from a passion to create something new. So, naturally, I came to movies.

I made this movie because it was the only way to include testimonies of the people who perform the Psychomagic acts. I needed them to write a letter saying, "I had this problem, so I did this Psychomagic act." For years, I had practiced Psychomagic with individuals, then with families, and then with whole countries, so I made a picture based on that.

But, without Pascale, I could not make this picture, because I could not make this film like a "director." I could not rehearse any of the shots in the movie. I needed the people we filmed to not sense that they were being filmed.

"The goal of the artist should not be to show himself as a narcissist would. It's for a person to show the value they have."

Montandon-Jodorowsky: We work together and we know each other very well, so making a film about Psychomagic felt very natural. It was important to show and share with the world that it exists and how it works, and for me to be a part of that. So, we didn't really need words or anything else to understand each other on this project. Making the film was kind of a Psychomagic act for us, too.

Jodorowsky: But it was difficult because we didn't know how each person we filmed would react. Some people came to me with the idea that I was a healer, and that they had to pay the healer: "He is a father figure." But it's not like that. This was really for the people. I did this because I love humanity.

I'm not in a war against psychoanalysis or against science. Science is necessary… it’s just incomplete. We also need to work with the spirit of a person—with their fantasies, their realities, and their sensibilities. Every person is a kind of artist and every person has something to say. The goal of the artist should not be to show himself as a narcissist would. It's for a person to show the value they have. That is what's healing: "I have value." When a person feels their inner value, they start to live. And that is beautiful.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: It’s important to know that everything in this movie is true. Alejandro can't say this himself, because he's humble, but he's a generous person and his kindness with people is real. He wanted to make a movie, but he also wanted to heal these people. So, every situation and every person in the movie is real, and their suffering is real.

NFS: You both asked the people who are featured in this film to be quite vulnerable. Even if they weren't filmed and you did this kind of therapy off-camera, they would still be in a very vulnerable position, so adding the camera only intensifies that. How did you both allow each person to feel comfortable during the process?

Jodorowsky: Well, I'm not a psychoanalyst. It's more like I'm a cook in a restaurant making a pizza or an omelet: I will make the omelet, but you decide whether you want to eat the omelet. It's not for me, it's for you.

I have millions of people who follow me on Facebook and Twitter and I wrote to them saying, "If you have a problem, send me a letter. I will see if I can do something for you or not." From these letters I got from Mexico, I chose two people and said, “Come to Paris and don’t worry, we’ll cover everything with our budget. Just know that it will be a healing experience. It's not acting."

Montandon-Jodorowsky: Part of the healing process is to be seen, to be listened to, and to be taken care of. So, it was important for each person to know that we paid for their travel, their hotel, and everything else. A big problem for many of these people is that they don't feel seen. They don't feel as if they even exist.

Jodorowsky: One person in the film I found on the street. He knew me from my work reading Tarot and he said to me, "I need you. I want to commit suicide. Can you help me?" I said, "Yes, I can help you. Are you a drug addict?" "Yes." "What drug?" "Heroin." "OK. I will meet you tomorrow for coffee." I gave him the address, he came, and soon after, Pascale and I took him on a plane to Spain to perform a Psychomagic act. It was an enormous adventure for him and for us.

I wrote a book called Metagenealogy, in which I explain that we cannot heal a person if we don't know his family life. So, I met with each person once beforehand to map out their genealogical tree, based on what they tell me about their brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, and grandparents. Then, based on what kind of family you have, I decide what Psychomagic act I will assign to the person. From there, we prepared for the act and decided which things would be important for each person—like wearing a costume, for instance.

"When you're shooting you can usually do something 20 or 30 times over, but for this film that wasn't possible. Every Psychomagic act consisted of one shot, because it's not possible to 'remake' a Psychomagic act."

Montandon-Jodorowsky: From the first day each person came to visit us in Paris, they knew that they would be filmed. It was never a surprise. They had to feel trust and confidence in us in order to do each Psychomagic act, so we had to create an atmosphere of intimacy.

These weren't the normal conditions of a shoot. When you're shooting you can usually do something 20 or 30 times over, but for this film that wasn't possible. Every Psychomagic act consisted of one shot, because it's not possible to "remake" a Psychomagic act. We had to make the camera feel as invisible as possible. If we put 3 or 4 cameras and lights everywhere, it would disturb the people we filmed when they're in that state of vulnerability. So, I filmed them, but with a tiny camera—and I was very transparent with them about what we were doing. I had to make sure they knew that I was not only the cinematographer but also Alejandro's wife—an extension of him. And as each person felt more confident, they forgot that we were filming.

Jodorowsky: Yes. We could not use set decor. No cinematographic light, no big camera movements. We also needed to shoot immediately because we didn't have any permits. I needed to capture the reality of these people I had met on the street.

But at the same time, the film is not a documentary. Documentaries speak about reality, but they show what has happened in the past. As we made this picture, we were not showing things of the past. We were making it right then and there. We wanted the audience to feel real emotions because so many movies essentially create fake emotions with actors—theatrical emotions. But here, we're showing absolute reality.

We shot for about 3 hours with each person. Then, when we cut the picture, we reduced all of what happened to an essential moment of truth. And from that, you have the picture.

NFS: There are callbacks to certain images from Alejandro's filmography in this film. Talk about the relationship between the imagery of his earlier works and the imagery of the Psychomagic acts in this film.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: I think Psychomagic: A Healing Art is important because it shows how Psychomagic is present in all of Alejandro's movies, since the beginning. It shows that there is no separation between art and life. This movie shows the unity between his earlier movies and the Psychomagic acts we filmed. By showing the unity between those two things, we can better understand the universe of Jodorowsky.

Jodorowsky: In all of my pictures, I was always searching for reality. When your mind is open, you naturally progress from one form of art to another, and eventually you come to something that never before existed. So, I was actually surprised when the idea of putting Psychomagic acts in my earlier films first came to me.

In El Topo, for example, my character has a 7-year-old son who buries a photograph of his mother. This is a rite of passage for the child, when my character says, "Now you are a man." And it is a Psychomagic act. It changed the child's life and it changed my life—it helped me learn to be a father because I didn't have a good father and didn't know how to be one.

Without a woman and man making love, you cannot make a child. I looked at the making of this picture like that. Our motives as filmmakers were good because we both acted as a father and a mother for each person who performed the Psychomagic acts. Pascal and I collaborated 50-50 on this film as a couple, based on our own experience. It's best to do it that way.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: That’s why people accepted being filmed—because they did not see a big crew working with us. They only saw a couple and they felt love and kindness.

"I won't make movies like most people, I will act like a poet. I express my ideas about the world as a healer would do. I'm not someone focused on having a script and a lot of money for some big industrial thing. No. I want to give something to the public."

NFS: You both explained that there were no rehearsals—no opportunities to "recreate" any of the Psychomagic acts by shooting extra takes. I would imagine that that's a different way of working than how you worked on your previous films, whose scenes are heavily constructed with color, lighting, costuming, and other production elements. Was this one-take approach freeing, or did it present new challenges for you as filmmakers?

Montandon-Jodorowsky: Regarding techniques, the work I did on the color was almost the same as for Alejandro’s previous films. We worked together on the 4K remasters of his earlier movies, but we didn't make them together, so I can’t say much about those. But when it came to the color of Psychomagic: A Healing Art, it was almost the same as the color work I did for The Dance of Reality and Endless Poetry. We worked on the color as a team.

There is not much difference between Alejandro's older movies and this one. In all of his movies, there is a journey between dreams and reality, but everything in them is truthful. As Alejandro said, you can see Psychomagic in El Topo, too. And at the end of Endless Poetry, you see him perform a Psychomagic act: He's healing himself by speaking to his father through his sons.

That’s why it was important for us to show that Psychomagic: A Healing Art is not really a “documentary,” but simply a film. It's in a category that doesn't really exist.

"I am not against industry. Industry is industry and it needs to be like it is. But it's not really art, because the goal is to make money."

Jodorowsky: Listen: I am not a moviemaker. I am a creator. I make all of the arts. I have been developing my version of the cinematographic experience for years to create a new kind of experience. There is nothing behind this project other than our passion to make a picture.

Every picture has a lot of problems before it can be realized: "We need to make money with the picture! We need to have a star in the picture! We need to imitate Joseph Campbell’s famous book, The Hero's Journey, where a three-act story is perfect! We need to write a script, respect the script, valorize the script! We need to plan the number of days and hours we will shoot!" That is terrible... terrible. Because it's dead.

The film industry can be good because they make movies for people who go to have fun and forget the world. But these images are fake. They are not reality. These movies are good for business and they allow people to have fun. But I arrived at a different conclusion: I won't make movies like most people, I will act like a poet. I express my ideas about the world as a healer would do. I'm not someone focused on having a script and a lot of money for some big industrial thing. No. I want to give something to the public. That is art. It's a form of healing for me, for my wife, for people who are ill, and for the public as well. I want to make people feel that live is worth living.

In the time we're in living in, only the material world is in place: dollars, yen, industry. Two of my films, Tusk and The Rainbow Thief, were made for the industry. But I couldn't do what I wanted with them. It became a big fight because I believe that movies are art.

NFS: You crowdfunded both Endless Poetry and Psychomagic: A Healing Art. When it comes to this struggle against the industry that you're describing, would you say that crowdfunding was one way for you to operate outside the industry?

Jodorowsky: I am not against industry. Industry is industry and it needs to be like it is. But it's not really art, because the goal is to make money. Money, fame, power. Once you join an industry you are like a politician. It's politics. That's the way it is.

A person of industry cannot do crowdfunding, because the people who donate their money to a project don't believe in the morality of "industry." [Laughs] They would say, "You are a big business, why do you need our money? You have millions! You can make a $400 million film!" A poor guy needs crowdfunding. An artist needs to be honest, and if you're honest you can get crowdfunded because you're not lying to your financial backers. You're addressing people who want films that are art and not commercial products. For me, it worked very well.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: The crowdfunding gave complete freedom to Alejandro, and strength, too. It's really something to know that lots of real people out there want him to make a film. That's very powerful.

Jodorowsky: I don't work for financial success. I want to have glory! When I make films, I risk catastrophe [laughs]. Fando Y Lis was a catastrophe in the United States. Today, you could release Fando Y Lis, but at that time, releasing a picture like that was impossible. I was attacked outside of the theater where Fando Y Lis premiered. Three days after the attack, I said, "Argh, they didn't like that. Well, I will go to Mexico and make a cowboy picture. And one that they will like!" With El Topo, I wasn't really making a cowboy picture. It wasn't a Western, it was an Eastern. But to Americans who saw El Topo, I became the creator of the Midnight Movie. And the only reason that happened is because I had only enough money to put the movie in theaters at midnight! But that was because I saw movies as an art and not as a way to earn money. I wanted to make art to develop my sensibility.

Throughout my whole life, the producers I’ve worked with only gave me money because they admired me. When I made The Holy Mountain, it was so weird: “I don’t have the money, so how can I do this?” But I had the good luck of John Lennon and Yoko Ono liking El Topo, and they said to my producer, Allen Klein, "Give Jodorowsky $1 million. Let him do whatever he wants, don't ask him or tell him to do anything. Give him the million." And then I had $1 million, and with that, I made the picture.

"The people we included in the film were experiencing real suffering. If we saw that people's motives were anything other than to heal themselves, we stopped filming."

NFS: You both mentioned earlier that Psychomagic is a form of therapy that’s rooted in acts. Were there other acts you performed with people that didn't make the final cut of the film? How did you decide in the edit which acts might be better suited for the film than others?

Montandon-Jodorowsky: Sometimes, people ask Alejandro to recommend Psychomagic acts that they can do themselves, but those acts aren’t always cinematic. The acts in the film had to be cinematic—visual in nature.

Jodorowsky: Whatever is in this picture is in it because it's an honest picture. If I faked what we show on screen, these people would not have a healing experience. With one woman who was depressed, I brought her to an old tree in a garden and told her to throw a little bit of water on the tree. She was an egotist, so I told her to do something for the tree. That was her Psychomagic act. I didn't give her any solutions for her problems because I didn't have any.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: But she was better after the act.

Jodorowsky: She was better, sure. But we couldn’t shoot her anymore after that. It was difficult because she was too self-conscious about it being an act.

The people we included in the film were experiencing real suffering. If we saw that people's motives were anything other than to heal themselves, we stopped filming. With one person, I could see that the only reason he was doing the Psychomagic act was to be in a movie!

Montandon-Jodorowsky: Yes. He did it for the wrong reasons. When it's fake, you can see it and it doesn't work.

NFS: Most of the film shows Psychomagic acts that are more intimate and focused on either individuals or couples. But toward the end of the film, you both organize a large group to perform a Psychomagic act together in Mexico as a form of public protest. What are your thoughts on how Psychomagic as a "healing art" can create a movement or social change?

Jodorowsky: I started with individuals, then moved to couples, then to families. And as I was making these people's genealogical trees, I realized that we're also living in an ill society. People are not really “individuals”—we are social creatures. None of us are alone. So, if a family is ill and we can make a Psychomagic act for that family, then we can also make healing art for entire countries.

But it is not political. If this was a political protest it would be a failure.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: The people in Mexico at the end of the film are young people—not politicians. It was young people who asked Alejandro on Twitter, "Please, do something, because things are terrible." So we created an act, and it was very positive because Psychomagic is a new form of protest—a positive way to protest.

Jodorowsky: This year, they cut down the forests in the Amazon and they're hurting our source of oxygen. So, I proposed on Facebook that we do something for the Amazon and millions of people did it. In America, a fantastic example of something like this is the man who went around the country planting apple trees. That’s a perfect act of social Psychomagic.

Montandon-Jodorowsky: None of us are alone. We might think we're alone, but we’re not. Every action we take has consequences, and those consequences can hurt people or heal people.

Your Comment

1 Comment

Effective Post

August 26, 2020 at 10:25PM