Jordan Peele’s Nope is a spectacle of horror filmmaking, all shot in large format.

I just saw Nope. It was phenomenal. Love it or hate it, you have to admit that every frame of the movie took advantage of Hoyte van Hoytema and his larger-than-life composition.

But what cameras were used to shoot this movie and why? And what can creatives learn?

A Larger-Than-Life Frame

If you know the name but don’t know why, Hoyte van Hoytema is the go-to director of photography for movies shot on IMAX and 65mm. The Dutch-Swedish cinematographer is behind Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Dunkirk, Tenet, and the upcoming Oppenheimer.

And he brought his bag of tricks to Nope.

In that bag was a whole lot of Kodak film and, of course, an IMAX camera. According to IndieWire, about 47 minutes of the final cut was all shot on IMAX, the rest being a mix of 65mm film on a Panavision Panaflex System 65 Studio and some digital 65mm, which we’ll get to later.

If we were to use one word? Expansive.

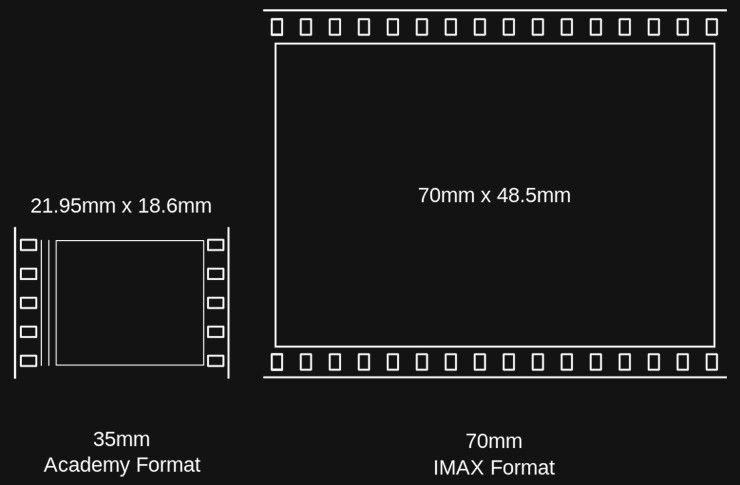

That’s the word Peele and Hoytema kept saying in all of their interviews. And that’s what the IMAX frame allows you to capture. Sure, you could get expansive landscape shots with a smaller frame size, but doing the same thing with an actor right next to the camera is a whole different story. Just look at the size of IMAX film compared to the old-school Academy Format.

With that format at hand, as well as the 65mm in the Panavision camera, the actors of Nope and the landscape behind them (as well as the UFO) could fit into the frame to create the expansive look Peele and Hoytema were looking for.

But the most interesting thing about Nope is how these types of shots were done for the gorgeous night sequences.

Reinventing the Wheel

We’ve all heard day-for-night, right? No, not the movie, the concept of shooting during the day and editing the footage to look like night in post. Well, Hoytema did just that but added something unique to convey the night look he was after.

While the details of the technique are still under wraps, Hoytema did divulge some of his secrets, which is where that digital 65mm camera comes in. According to what we gathered from several interviews, the night sequences were shot on a specialized camera rig with roots in 3D.

But instead of two cameras shooting into a prism to create the illusion of three dimensions, one camera was presumably the Panavision System 65 and the other a digital 65mm camera modified to shoot infrared, which created the unique effect of darkening the sky. These two frames were then combined in post, allowing for Hoytema and Peele to choose what part was traditional film and what was infrared night photography.

Cool, huh? The photo below was shot in infrared during the day.

If you want to see how Hoytema's camera rig technique could work, this video comparing the ARRI Alexa 65 to the Alexa Mini shows the concept in action.

Learning from the Best

So what did we learn? Shoot on an expensive IMAX camera and build your own infrared camera rigs? Sure, but we can pull some more nuggets of wisdom to use on a budget.

Firstly, we can consider our frame in layers instead of one single image. With that in mind, you can implement the same concept to, let’s say, lighting. Film Riot used multiple layers to light an actor at night, after which they removed the light in post.

Secondly, we can think of the size of the frame and how it affects the intimacy of our composition. While larger frames can be more expansive, smaller sensors or film sizes can create tighter shots that can help create closeness or familiarity with your characters. They’re also cheaper, so why not use something smaller, like Super 16 or Micro Four Thirds?

The Panasonic LUMIX GH6 recently came out with an MFT sensor, and you can get an OG Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera that shoots Super 16 in Cinema DNG.

Even though we may not be able to use the expensive tech we see on big blockbusters, creatives can still learn a thing or two from how they are used. It doesn’t matter if you’re spending millions to shoot your movie or the pocket change you found in your couch cushions, we all rely on the same fundamentals.

Your Comment

3 Comments

Day for night technique sounds a lot like what was used here: https://nofilmschool.com/ad-astra-movie-interview

July 27, 2022 at 11:17AM

You're exactly right! That same technique was first developed by Hoytema for 'Ad Astra.'

July 27, 2022 at 12:23PM

I don't wish to be negative, but there is a lot of misinformation about large-format going around last few years, and this article is really romanticizing large format.

Simply put, nothing changes in large format except in film, the grain gets smaller and the lenses have a harder time covering so much film or sensor. Thus you get fun and cool looking effects such as vignettes, edge softness, distortion, and because a large format lens may have a larger aperture all other things being equal, shallower focus.

Steve Yedlin, A.S.C. has written a number of essays debunking this, and as an owner of a MiniLF, I can tell you my experience with it supports Mr. Yedlin's assertions. You get a modern enough lens on the MiniLF that covers without vignettes, softness, and distortion, and it looks just like the ALEXA Mini I owned previously. I'll link Mr. Yedlin's writings, and also link a mirror box rig comparison video of Alexa 65 vs S35:

http://www.yedlin.net/NerdyFilmTechStuff/AnotherLargeFormatArticle.html

http://www.yedlin.net/NerdyFilmTechStuff/MatchLensBlur.html

https://vimeo.com/444951736

The Vimeo video shows the 65 is nothing but lens distortion and vignetting (which looks awesome). It's all about the technical proficiency (or lack thereof) in a lens for large format...there's nothing inherent about a wider shot on a 50mm that is magic.

July 28, 2022 at 11:17AM