The Invisible Man is a throwback piece of intellectual property, but the team behind it used some modern tools and techniques to make a sleek, updated, and thrilling version.

The Invisible Man broke through with a unique approach to the story. The priority was to stay practical, keep the action clearly visible, but also haunting and no less thrilling. Jonathan Dearing and Stefan Duscio were charged with bringing the VFX and cinematography into balance in pursuit of these goals.

How did they do it? How do they work together and with director Leigh Whannell? What are their preferred tools and methods for production but also for planning?

We were able to talk with Dearing and Duscio about all these things and more.

No Film School: How did each of you got involved in the project initially?

Jonathan Dearing: I've got a history with Leigh [Whannell]. We did Upgrade together, which is a sci-fi thriller he did in 2017. We instantly bonded and shared the same philosophy about shooting as much practically as we could, using visual effects to support and add where it needed to. It worked really well for Upgrade. So when he walked back into town with the next script in his hand... The Invisible Man, we instantly were on the shortlist. I had a quick meeting and we picked up where we left off two years earlier on the previous film.

Stefan Duscio: I met Leigh on a little film that we did in Melbourne, Australia called The Mule. It was a film that he co-wrote with his old friend Angus Sampson. And they subsequently both acted in the film. I got to know Leigh better and discovered that we had a lot in common. We discovered we both studied the same course at university, which was media arts. But we had a lot of similar feelings going through that course.

After The Mule, Leigh started telling me about Upgrade, which I was very excited about. It was one of the fastest scripts I've ever read. Such a fun read. And Leigh and I hit it off on that and just stayed in touch. I was very excited that he wanted to collaborate with me again.

"We want to make movies based on story and tension, and with that comes the reality of shooting things as practically as you can." - Jonathan Dearing

NFS: Upgrade has a sci-fi element that's incorporated into a world that's supposed to feel grounded. Is that the way you guys came at Invisible Man as a team again, too?

Dearing: Very much so. Obviously, Leigh understands and appreciates the benefit of working with practical set pieces and real locations, and would definitely err toward that rather than sitting in a studio on a green screen set or stage. So, he always wants to approach things practically.

I step in as the support for the stuff he doesn't know how to shoot practically. If they can see a practical way, definitely he's going to want to try and achieve that in-camera. A lot of us from that age group want to do that. We're not 20, 25, 30-year-olds that want to show how we can animate the next Incredible Hulk. We want to make movies based on story and tension, and with that comes the reality of shooting things as practically as you can.

NFS: In terms of where you guys cross over, how much of it is a team effort to figure this out?

Duscio: It's very collaborative. We spend a lot of time, Leigh and myself and Jonathan, in pre-production talking about how we're going to shoot the sequences. I'm really big on pre-visualization and storyboarding and shotlisting. On a project like The Invisible Man, every department is hungry for information.

You can't improvise as much as you might in other films. You need to pre-visualize and conceptualize as much as possible, so you can engage and inform every department, whether it be Jonathan's visual effects department or art department. Everyone wants to know where the camera's going to be, what it's going to be doing, and how you'll achieve these sequences.

I encouraged myself and Leigh to either shotlist, storyboard, and photo board even. For some of the more complex scenes, we would take a stand-in or two to the real locations where we're going to shoot the scene and photograph how we would shoot it. Then we would make a PDF from that.

And then on that document, we could analyze it with Jonathan and say, "Look, this shot, the camera's going to be locked off, so that's fine. We don't need to do anything overly complex here. However, if this shot requires a moving camera, then it's going to need to be motion-controlled," for example. It enabled us to have all those conversations early on.

In some of the more complex sequences, for example, when Cecilia's character is escaping from the psychiatric ward, we shot that sequence on a Canon 5D with some stand-ins.

Then they cut it together. Jonathan annotated that digitally, and said, "Look, this shot needs to be achieved this way. This shot needs to be achieved that way." And we all collaborated and discussed it together.

NFS: Do you shotlist and pre-vis everything, or do you just pick the key things that you feel like you really need to go through? Also, what are your preferred tools for that process?

Duscio: On films I've done, I've only ever had time to shotlist and storyboard with the director the key sequences that involve a heavy amount of stunt work or visual effects.

On Invisible Man, we did as much as possible. There were a few things in there that we didn't shotlist, because we wanted to be more informed by what the actors might do on the day. Seeing Elisabeth [Moss] interacting with nothing essentially, in a room by herself... we might say, "You know what? Let's see what Elisabeth does and design the coverage around that." Let's be inspired on the day by that.

NFS: Jonathan, when you get involved, you're involved in the planning and the discussions with the storyboards as well?

Dearing: We'll have a sit-down and a powwow about how we're going to achieve something. That can rapidly expand to most of the team at a big roundtable where we are talking to special effects, as well. If it's a gas bubble exploding, or a fire that has to go up, we're hearing directly from [the practical effects team] on what equipment they've got, whether they've got smoke machines, and what they can achieve practically. So, we very quickly whittle down what effects are going to be special effects and what effects are just not possible practically.

As for tools, I use Photoshop for concept frames, and then if I am lucky enough to get some pre-rollover of the rehearsal on a Canon or any non-production camera, we'll take it into Final Cut and start editing it together. Either I or the editor will work out timings on how a camera move works, or whether something needs a more elaborate technique or visual effects.

Scenes with the motion control rig were unrehearsed.

"...a big, big part of why it's so successful, is because the motion control rig is so unique in its movements, and following what the action was." - Dearing

NFS: As far as the motion control rig goes, can you explain a little bit about it and how you used it?

Dearing: It worked on so many levels. I'll let Stef talk more on the practical stuff in a minute. From an artistic level, it has this very deliberate way the camera moves, and how Leigh and Stef went away from your traditional action movie, where you're just led to believe that it's so frantic and frenetic that "shit is going! shit's going down!" and it's beyond your mere human capability to see it all.

The motion control rig does incredible, crazy, acrobatic movements, and because it's been rehearsed and because you know where the camera's stopping, someone's head is right in the middle of the scene for the whole shot. And then it's doing a 180-degree flip around to the next thing that we're supposed to look at. Because it's all choreographed and worked out.

It has this incredible energy, but the audience can see everything that's going on. Depending on Stef's choice of exposure and frame rate, we're controlling the amount of motion blur. I always felt like the action was very visible. You could read exactly what was going on. I think it was a big, big part of why it's so successful... the motion control rig is so unique in its movements and following what the action was.

Duscio: I was lucky enough that Leigh had been mentioning The Invisible Man quite early on when he was writing it. I spend a lot of time in the commercial word, as well. I've used it on a few commercials and gotten familiar with it.

On every commercial, I was telling them about how we would shoot Invisible Man with this thing. Those commercials were a bit of R&D for me. When Leigh and I started working on Invisible Man a bit more, I would show him these commercials that I'd done and tell him about motion control and how that could help us. He fell in love with the idea of having these longer takes in the film, rather than sequences of fast-moving coverage where you could hide and do tricks.

It's something we've all seen many times before. But what I thought would have been more haunting is to have the camera just wander slowly around the kitchen and see the character be affected by this invisible force.

We're all used to seeing these very messy fight scenes where you don't quite see what's happening. I myself have shot a lot of them and they're not that exciting to shoot. Sure, it's kind of fun on the day to chuck a camera on your shoulder and throw a camera around during a fight scene. But ultimately, they're not that engaging to watch in the edit, because you're missing so much detail.

One of the things that excited us about the motion control rig was how precisely the camera moved. It reminded me of something David Fincher said about his moves in Panic Room, which was it was like the camera was preordained to do what it was doing. It was this sort of otherworldly force, wandering around the room. It's called presence. And motion control felt like that to us.

And it took us a while to find that language because sometimes we went a bit too far. So, we dialed it back down into somewhere between a real-world feel and a robotic feel. It took a while to program those moves, because sometimes it stops so precisely, or moves so sharply, it didn't feel right. We needed to teach the robot a little bit of humanness, and then when I was operating on a dolly, I tried to operate like a robot. So, it was like we were trying to meet somewhere in the middle.

NFS: That's funny. You had to find the middle ground between you and the robot.

Duscio: Exactly.

NFS: Just talking about the look in general, I know you used the same lenses and camera that they used on 1917, for example, and yet to such a different end. A lot of filmmakers are using similar tools or the same tools, but you could still end up getting such a varied look. Can you talk us through a little bit about how that worked out, or how you achieved that?

Duscio: I've shot a lot of films and a lot of commercials on the ARRI Alexa family of cameras. And maybe a year before The Invisible Man came around, that ARRI had released the Alexa LF, and I was very excited about that. I shot a bunch of commercials on it. I've shot a couple of things on their lenses, ARRI Signature Prime Lenses, which I really enjoyed.

And by the way, I'm a huge fan of Roger Deakins' work, particularly his work with Denis Villeneuve.

When I read Leigh's script of The Invisible Man, I felt like it had a similar thriller flavor to those films. And I thought I could lean into that thriller language and shoot on these modern ARRI Signature Prime lenses. It felt like the right look and clarity of picture to me. It just felt like a modern thriller.

It didn't need any kind of trick lenses to give it a Deakins feel, for example, or an aged feel. It felt like a very contemporary story, and I should just lean into that modern image. The combination of that sensor and those lenses would give it that texture. I worked very hard with my camera and lighting teams to give it a very cool, crisp, kind of modern stealthy look to the film.

Leigh and I really wanted very still camera work. We didn't want to do much handheld work. We wanted to be on a dolly or a tripod as much as possible to keep the frame very still, so it'd encourage the audience to look around the frame.

'"...lenses become some of the most important decisions for the character of the image - Stefan Duscio

NFS: Traditional eye-level, classic framing?

Duscio: Exactly. Exactly. And that was one of the things I really admire about Roger and Denis, is their boldness to be simple. Restraining the camera requires a lot of confidence in some way because film actors tend to want to use the camera a lot more and give scenes more energy than they may need.

The power in his script and in Elisabeth's performance meant that you could just hold a frame on Elisabeth with a still camera, or hold a frame on a still part of the room, and embrace the tension.

NFS: It sometimes feels like you framed scenes in ways that there was another person there... who wasn't there. Right? Like you treated it like there were multiple people in the shot.

Duscio: Absolutely. That was a directive of Leigh's very early on. He was like, "I want compositions to feel incorrect. I want to feel like you've put Cecilia, on one side of frame, and emptiness on the other side." And we did aspect ratios testing to see what aspect ratio looked better for negative space. We compared widescreen with 1.85, and decided that widescreen felt better because you just had more negative space to play with when you're placing the character on one side of the frame.

NFS: Yeah. Roger Deakins always speaks to the idea of, "Let the story do the work." Don't get in front of it, or draw attention to something else.

Duscio: It's interesting, because the last film that JD and I worked on with Leigh, Upgrade, we shot on a standard ARRI Alexa camera with vintage Panavision anamorphic lenses from the 70s. So there would have been a lot of distortion on those lenses, for example. But that was right for that story. Lenses continue to be one of the most important decisions DPs and directors make on production because certainly, the camera sensors out there arguably can be interchangeable, in a way. You're splitting hairs between some of these sensors now, but lenses become some of the most important decisions for the character of the image.

NFS: In terms of lens choice, how does it affect things on the VFX side, Jonathan. Did using these modern lenses without distortion alter your process?

Dearing: I'm learning the language of that particular lens. There's always lens distortion, but on these Signature Primes, it's incredible how little lens distortion there is. Even in the previous film, I had the anamorphic lenses on it, and there was a complete lack of traditional lens distortion on those, as well.

With the modern techniques for making lenses, it's more impressive each time I see a new lens come off the shelf because I was literally A-B testing those Signature Primes, and going, "Hang on, show me the one with the distortion and the one without." It was almost hard to pick it. In that instance, a big part of our job is removing the lens distortion when we're doing a full CG shot.

NFS: Can you take us through that process?

Dearing: Say we're extending a building, and you've got really straight lines. Obviously if the camera's panning through all that, then there's an amazing amount of warping and distortion that's going on, we have to remove that. Then we have to create our CG to get everything to line up straight. Then, because we've studied the amount of distortion, we add that amount of distortion back on the final comp shot. So if there's less of that original distortion, then there's less chance that we're going to be off.

It does become easier, but it's not a huge amount of impact. It's just something we have to pay attention to and then adjust our settings in the control software to facilitate a perfect shot. Which really is our end game, so it's just about changing directions slightly.

I notice the noise in some of the channels starts to change it, too. I guess it's the actual camera body itself. The darker a shot gets, the more grain there is in a particular channel.

It was the blue channel on this film. It was really buzzy, like probably twice, or even three times the amount of digital grain that other channels had. We'd have to study that, and make sure that when we added our grain back on to a CG element, that it matched exactly.

NFS: I wanted to ask about the decision-making and the creation of the "Invisible Man" himself.

Dearing: It was a roundtable in pre-production. I met with Leigh and the art director. We all came armed with concept frames and every image you can imagine of every superhero suit that we've ever seen. And within two minutes, it was like, "Throw all those away." None of them struck a chord with Leigh, and there wasn't anything that he really wanted to do, go anywhere near a kind of superhero vibe.

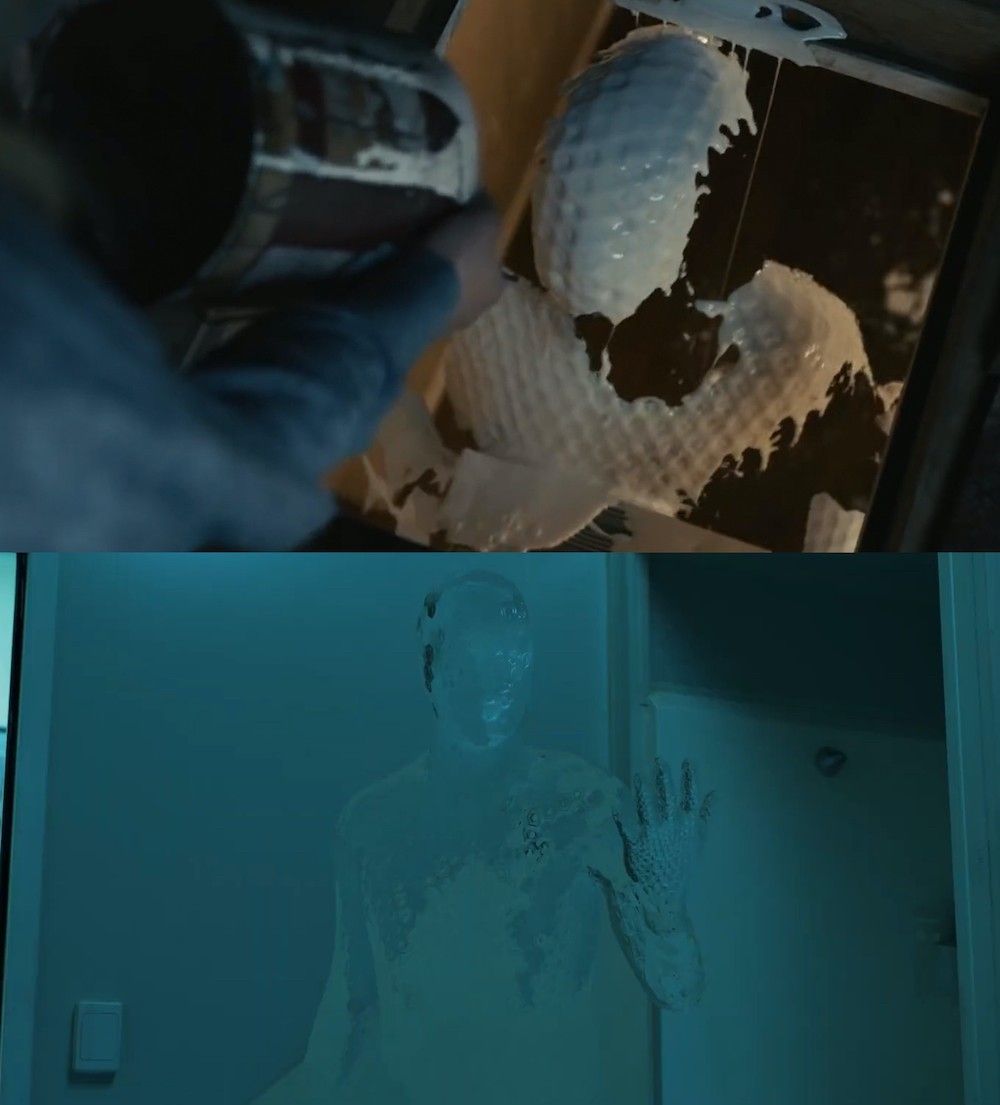

But a lot of the underlying suits are very tight-fitting to show the form of the athletic prowess of whoever's wearing it. So we quickly realized that we wanted something that was pretty tight fitting. And then, there is a bit of a link to a previous film, Upgrade again, where hexagons were quite a starring part, a big scene in a lot of the technology that was in it. So, we quickly started looking at those sorts of shapes again.

We kind of quickly arrived upon a wetsuit that was made up of very small hexagons that housed a lens in it. I think we walked away from that initial meeting with the basics of what it ended up looking like, from an aesthetic, physical suit point of view. We knew the guys to talk to in Sydney that could make that sort of thing.

It really didn't deviate from that original meeting. Within a couple of days, we had an image that we'd mocked up for what we thought it would look like, and that's the way it went. We knew that what we had to do from a digital effects point of view was to try to figure out how all the tech could fit inside such a small space. We kind of went macro, testing what the lenses looked like when they move and the mechanics behind it that are pushing them up and down.

We showed something to Leigh while we were actually still shooting, and he loved it. From that point on, Leigh was very comfortable that we were going to be able to pull it off as a digital double in most instances. Obviously, in the car park in the rain scene, you saw a lot of it. And yeah, it was pretty effective.

NFS: I'm sure it was nice to know that everyone believed it was going to work.

Dearing: We felt the pressures of the schedule because we knew that there was a hard delivery date that wasn't really going to shift. In fact, it came forward. Luckily enough, it did come forward, because I think they timed the release of the film in the nick of time. But we knew that that schedule was tight, so I was having conversations on a daily basis with the 3D CG team.

NFS: People forget that release dates create, especially with VFX, a whole other level of pressure.

Dearing: Yeah. Absolutely. You're subject to so many market forces. You have to move very quickly and have to adapt to the ever-changing condition and the nature of the job. That is the job.

Up Next: How Roger Deakins Filmed '1917' in One Shot*

Stef and Jonathan referenced the work of Roger Deakins, we had a chance to speak with Deakins back in December when 1917 was released, and similar to this piece he walked us through his entire process. If you want more DP insights, we also spoke to Sam McCurdy who lenses Lost in Space for Netflix, among countless other high budget series, including a very important, and influential, episode of Game of Thrones.

Your Comment

1 Comment

So this is how NFS makes money.

March 31, 2020 at 3:55PM