Finding inspiration during production can be intimidating, but Ashley Sabin and David Redmon tell you how to find the greatness in those in-between moments.

In an era where streaming is king, the filmmakers behind Kim’s Video remind us why we love movies and what power the video store had.

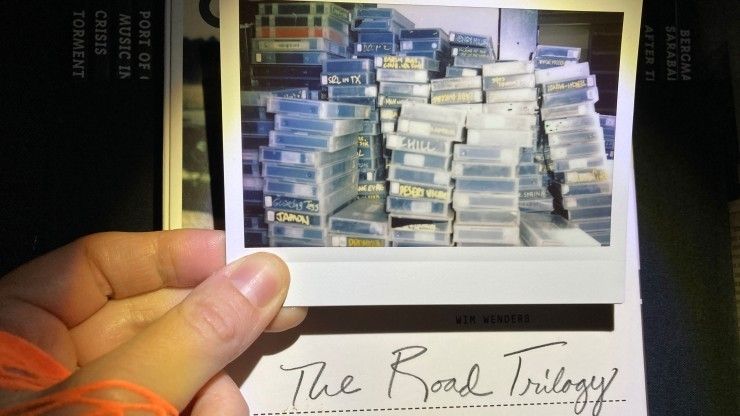

But before streaming platforms took over the home entertainment market, video rental stores were the place to go. Kim's Video, however, was different. With more than 55,000 beloved and rare moves to choose from, Kim's Video flagship store in St. Marks Place was an essential stomping ground for cinephiles, filmmakers, and anyone who enjoyed great and strange art from around the world. Filmmakers like the Coen brothers, Quentin Tarantino, and Martin Scorsese were proud members of Kim's Video, even though the Coen brothers did rack up an insane amount of late fees.

Then, facing a change in the industry, Kim's Video founder, Youngman Kim, offered to give away his collection provided that it stayed intact and available to Kim's Video members. The archive found a new home in the small Italian village of Salemi, Sicily. How did this collection end up there, and what happened to all those films?

In Kim’s Video, filmmaking duo Ashley Sabin and David Redmon track down the remains of a beloved video store and find a way to salvage what remains of the historical landmark. The documentary is unafraid to pull back the curtain and allow the audience to sit with Sabin and Redmon as they navigate their feelings and obsessions. As the story begins to dive deeper into that weird space where reality and film live together, we can’t help but celebrate the passion for filmmaking and the landmarks that made us want to become filmmakers.

Sabin and Redmon, who dress sharply for our interview, sat down with No Film School via Zoom before Sundance 2023 to talk about navigating the complexities of their documentary, when to listen to those creative voices in your head, and how to trust that you are in the right place at the right time.

No Film School: I know that indie docs are often incredibly difficult to put together, but your style and undeniable passion for the story comes through beautifully. You both wore multiple hats in this film as directors, screenwriters, editors, and producers. I'm curious, can you tell me a little bit about how your collaboration started and what it looked like on this project?

Ashley Sabin: It's like sometimes husband/wife, too. It depends on the day, doesn't it?

David Redmon: We move around a lot, as you can tell. We're in New York. We lived in Brooklyn. We lived in Montreal. We lived in England. We lived in Marseilles. We lived in Maine. We just happened to be in England, and we both received the same email three times. I deleted the emails because I thought they were spam. I thought it was a joke. It said, "Kim's Video is going to come back." That sparked our interest. Ashley said, "Did you get those emails?" And I said, “Yeah. I deleted it because it's a joke. Kim's Video is gone."

When that happened, it corresponded with our interest in wanting to make a movie years before when we were making Girl Model.

Sabin: We had been thinking about it.

Redmon: The voices had already been speaking to us. We had just visited [Ashley’s] parents' house where we had put all the movies that we collected from Kim's in the basement. We were opening the boxes and touching them and this flood of memories, this flood of voices, came to us and continued to speak. So, we said, "What the heck, let's try it."

That's how it came together. It was just a series of events that we asked to put the patterns together.

NFS: I know that film lovers and filmmakers have a very strong connection to their video stories. When you heard that Kim's Video was coming back and these memories flooded to you when was that moment you decided that, "I need to pick up the camera and tell a story?"

Sabin: What David was talking about, with the email, was a presentation that was going to happen from one of the organizers from Italy, and how they got the collection over to Sicily. Her name's Franka, and she was doing a presentation on what happened from her perspective. When we went and sat in on the presentation, we got the arm hair-raising moment. So much of what she talked about felt like we were immediately teleported back to the people that we used to be, in a lot of ways, at the beginning of making films. Our roots. We were reconnecting to our roots.

Redmon: Well, Kim's Video was from our film school.

Sabin: We both left [the presentation] without saying anything, then, after the presentation. we said, "We have to get in touch with Mr. Kim.” And we couldn't. Franka kindly gave us his email, and I emailed him, and I said, "We would really like to tell your story and figure out where the collection is now."

Redmon: It wasn't an immediate response.

Sabin: But when he did respond, he said, "You caught me at the right time. A lot of people have approached me to make this film and I said no in the past, but I want to do it now." So, it was just the magic of the universe, in a way, where we were in the right place, he was in the right place, and it came together.

Redmon: Before all that happened, we went to Sicily.

Sabin: No.

Redmon: No, not at all. We wanted to start in Sicily. Who is this guy? Why is he trying to rent a movie in Sicily? Does he really break? What happened? Was the door unlocked? Did he break in? Did he force it open? When the alarm went off, we wanted to flash back to Kim's Video and all the archival footage. We wanted to introduce Kim in that way. That's how we had structured it for a long time, and it just didn't work.

Sabin: Without voiceover.

Redmon: Without any voiceover. None. It just didn't work, so we continued to edit and re-edit until we came up with what you'd watched. It took years. It was a six-year project.

Sabin: We edit as we go through. That's typically our style. From the moment we start shooting, we'll start editing that scene, so things are slowly building. Then, as with anyone who's sculpting something, it transforms into different shapes, and then you're like, "Well no, take that left side off because that is not how it should be and add on more over here." It is like a six-year edit, which is painstaking.

Redmon: I still wake up every day wanting to make changes and add more. I went to Sicily just the other day, two days ago, to show the movie to the people in the town. Afterward, there's this guy who also helped with the making of the movie, Fabrizio, and he said, “You know, when you go under the bridge with Scarby, what you really need to do when you back up is, hard cut to a movie of somebody [spraying bullets from a gun] to really bring home the point."

I said, "Damn, Fabrizio, that's a great point, but we can't do that now. That's a great idea. It's so comical." He said, "That's why I'm telling you this because it is comical." And he said, "And I don't understand your intent under the bridge. Are you serious? Do you think you're going to die? You seem paranoid, but it's also kind of funny." I said, "Yeah, I think it's all those things." He said, "Then you gotta cut to you just getting shot. Boom, boom, boom." What's he trying to say here?

Sabin: That doesn't sound very comical to me. I think that's scary. But in retrospect—

Redmon: I thought it was funny.

NFS: It's funny in retrospect, but watching it at the moment, I was very nervous for you. Then it hard cuts to the next scene, and I am still recovering from my fear for you. But, that six-year editing process does sound painstakingly tedious.

Redmon: We had help at the end from Mark Becker. He did come on at the tail end for the last two months.

Sabin: And it made a big difference, bringing in an outside person, and just someone who's a talented editor.

Redmon: That's what I also said to Fabrizio after he saw the movie. I said, "If you notice, there's a bit of distance between us, and it made you very frustrated." That's just what I have to do. I have to be detached, but also close. And I know there's a gap between us. But now it's over, and we want to move on to the next project, and we want to make a fiction movie.

As we're making the movie, it's, “Who do we trust? How do we trust this person?” We're constantly wondering, "Do they have ulterior motives?" And they're thinking the same thing about me or us.

Now that we want to make this fictional movie, it's different.

Sabin: It's a fiction movie based on the making of [Kim’s Video]. It's directly connected.

The nice thing is because we are partners in projects and partners in life, we go through ebbs and flows, where one of us hates the project and the other one is the cheerleader, and vice versa. It allows for one of us to say, "Okay, I'm done. I need to check out. I can't edit this anymore." And the other person comes in, usually deletes what the other person did, and then we get into an argument about it. Our partnership and how we collaborate are critical to the momentum that pushes us forward.

We've been doing it for a long time. We started collaborating in 2005, so we know where our trigger points are and when to step back and when to let the other person have some space and all that. It's really important.

NFS: Because the editing process took so long and was originally done without voiceover, at what point did you realize that element was necessary?

Redmon: I think it was right around April of last year. Is that right?

Sabin: It was only a year ago. Throughout the process, I was pushing David because I felt like there were so many great moments of what he collected, so you would hear his voice and the people in front of the camera that would directly have a moment with the person behind the camera, which is David. I was pushing a lot of that stuff to be in the movie, and he was always pushing back.

We like to trust our audiences. That's something that, within our storytelling, we believe that audiences don't need very much to glean a lot. But in that case, the cut that we had where there was no narration, was really hard because it's such a strange story. It’s complex with many people and different countries. It was really hard for the audience to put the whole story together. It wasn't congealing. They kept saying, "Why? Why Kim's? Why go there? Who cares?"

Through David's narration, the “why” became clear. Why for us, then the why for culture, and why do people care about things that are lost and trying to find them? It was a light switch at that point, and then it was just a question of how much to put in of his voiceover when to pull it out if it's too much, and the delicate balance when you start writing voiceover.

Redmon: I'm glad you liked that tiny moment. We wanted to extend it. At the end of the film Close-Up, the motorcycle's going, and the sound is missing. That was a hard cut. A motorcycle drove by [when we were talking] with Mr. Kim, and we had cut to that scene. It was all about these missing moments of, exactly what you said, what happens behind the scene, the making of, and how to integrate that into the movie.

What we were trying to do also with that handheld scene is, not only to give it some tactile expression but tie it in with the voices as well. So much of movie-making is not only about the image, it's about the unseen. It's about the voice. It's about the sound. It's about what we hear and what we present to the audience through sound. Through the oral. Not the oral, the a-u-r-a-l world as well. Holding that up is an indicator to acknowledge sound and the importance of sound and voices as well.

NFS: Are there any lessons from the process behind Kim's Video that you're going to take with you into your next project?

Redmon: Oh my gosh. If Kim's Video was our film school, then making this movie was... We learned so much. We learned how to negotiate. We learned how to trust the world when it gives you material when it gives you voices, and how to listen to voices and make sense of them. I know it sounds a little strange, maybe. A lot of this movie came together in-between spaces. In showers. In dreams. In waking up. In walking. In jogging. All these in-between spaces when we're not actually sitting down in front of the computer. We always had a notebook or a phone with us to take these notes. Many of these scenes in the movie are derived from those moments, and that's what's so interesting, to me at least, talking about the making of. We learned how to listen.

Sabin: Well, I also feel like it was just being at the right place at the right time. The fact that that front door was even open. It feels like it shouldn't have been open. That front door should not have been open. Why was that front door open?

Redmon: Was it locked? But I love the ambiguity. You don't know.

Sabin: Yeah, you don't know. But there are so many moments like that that happened in the production. Things that should not have happened did happen. We were light on our feet, and we went with it. It was this almost magical place to exist in, where you just were trusting that unknown. That unknown was like a scary place to be in, especially when you're trying to tell a story and you want something rational, but it impacts the storytelling because it allows us to explore this place that is unexplainable and is dreamlike and cinema-like. That strange world exists between the two.

David would have crazy dreams in the production. Wake both of us up in the middle of the night and just be like, "I had this dream." Then I started feeling like, in the production, “Is that a dream or did that actually happen?” Because there was so much going back and forth between the two.

Redmon: And the movie's like a feverish dream as well.

There's the same shot twice of a woman waking up. In that movie, when she wakes up, the situation gets worse. I'll give you a specific example, going back to your previous question. The time in which I approached the door was haunting. That was a phantom. My body elevated and I listened to it. When I got to Salemi, I went on my own. I didn't have a smartphone. I had a dumb phone. I never had a smartphone until 2018.

What happened was, the voices told me, "Pick up your camera, and record." I said, "Why?" They said, "Just do it. Just trust us. It's important." I said, "Okay, fine." So, I just turned it haphazardly, recording everything, and went all the way around the building. I had no idea where Kim's [Video] was. I didn't know where the sign was there. The ground was burnt. There were bones on the ground, burned out. There were discs burnt. When I turned that corner and saw it, my whole body tingled. I said, "Oh my gosh, this is it." You see the filter, what's it called?

Sabin: The white balance.

Redmon: It just floated me into that door. I grabbed [the door handle], and it was the only door in that entire facility that opened. I felt the [wave of calm] coming. When I went in, that's when the movie spoke to me. I said, "Oh, those are the voices. That's why." It's those kinds of moments that, as a rational person who studied criminology and is supposed to use reason and rationality, you had to throw all that out.

This is what I mean by listening to voices. Listen to these irrational moments. That's just one particular moment, right there, as an example of what I was talking about earlier. And that happened. That's the whole movie right there, just carrying me. It just told me where to go, so I would go. It doesn't make sense, but it made sense to the voices telling me.

NFS: And if he didn't go in and the alarm didn't go off, you would never have met the composer, which is so fantastic. I saw his name in the credits, and I was like, "They hired him!"

Redmon: Yes. Yeah, he's the person who also showed up to see the movie the other day. Enrico [Tilotta] is amazing. Again, we're in a car, just recording, and he just happened to have that USB stick that he puts it in to shut me up. He said, "Horror movie." I was like, "Oh, horror movie. Oh no. Where are we going with this horror movie?" Then we get to know each other, and lo and behold, he starts making music for the movie.

NFS: Life is truly so strange. You can never put into words how life works out and its mysterious ways. I know there are challenges with any project. If you had to pick one, for each of you, what was the biggest challenge of production or the process, and how did you overcome it?

Sabin: I think for me, I, at a certain point, gave up on finding a home for the collection, because that took about a year and a half. It was during COVID-19, the height of COVID, and we had contacted so many institutions. We got far with Vidiots out in LA, and that was the tipping point for me when that fell through. I just thought, "This is it. It's going to die. This collection is going to rot there, and this is going to be the most depressing movie about trying to find something, finding it, and then just watching it decay."

Redmon: Do you remember what happened?

Sabin: You kept saying, "Don't worry. We're going to figure it out." I was like, "We're not. We need to give up. We just need to give up. We were putting our lives into this and we're hitting a wall.” That's a perfect example of our partnership.

Redmon: What happened is, I woke up. I couldn't sleep. The whole movie, I just felt beat up. So, what happened is, I woke up at two o'clock in the morning, unable to sleep again. I thought about it, and I started thinking, “Okay, let's just look and see if there are any new cinemas opening.” And there it was. So, we got in touch with the Alamo Drafthouse through a person named Josh Schafer. Then, he put us in touch with Tim. We pitched it to Josh, and Josh said, "I have no doubts, Tim will love this. I'm going to put you in touch immediately."

Sabin: Then it wasn't immediately after that, because we had to negotiate with Salemi, which had their wants or desires that they wanted from the agreement. That event wasn't immediate. So, I would even say, until the collection was on the cargo ship in the containers, that was a tough part of the production for me. You seemed okay at that point.

Redmon: Well, then the hurricane hit and it trapped the container for 10 days, and I thought, "Oh my gosh, what's going to happen?" But we decided not to put that in the movie because you already had the fire.

Sabin: That's biblical.

Redmon: That's Mr. Kim's movie, one-third. It's in the movie. And that's based on Dante. So, it is interesting, these different elements. You've got the fire. You've got the hurricane. All these earthly and spatial elements went into the making of this movie. Yeah, it just got stuck. It got flooded, but no water got inside, and then it was delivered.

NFS: That's so great. What a happy ending to a very stressful situation toward the end there. Do you all have any advice for any independent filmmakers who are looking to make their first feature-length documentary?

Sabin: David and I just pick up a camera. We learn the program. We just do it. That sounds cliche and strange, but doing it in our DIY way, which is a hard place to exist in now with the way budgets are and cameras and all that, makes things very slick. I would say DIY, all the way because it gives you freedom, but you also need the right collaborators. The people that also believe in that way of existing. Because once you have the freedom to tell the story that's inside of you, that's everything.

For me, it doesn't matter if your budget's $300,000 or if your budget's $20,000. If this story's there and the heart's there and the right places and you got a good team around you, then you'll find the path. I think it's just that combo deal for me.

Redmon: I'm hesitant to give any advice, but what we learned is to put ourselves out there. We met people like Enrico, but we also meet people and we ask ourselves, “Why did we let them into our home?” And it has nothing to do with any of the people involved with this movie here in the credits. It's not that. It's people who, it's very difficult to say, look at you and they think of opportunity. It's hard for us to not trust people because we have a tendency to trust and we want to trust. So, there's that radar that we don't have, and that's something that I wish I could do more, to learn how to say “stop” and “no."

Your Comment