What do The Whale, Sony VENICE, and cocktails have in common?

Director of photography Matthew Libatique has built one of the most impressive resumes in Hollywood. From working with Darren Aronofsky (a longtime collaborator) and Jon Favreau, Libatique has seamlessly hopped from arthouse to blockbuster. He’s even worked with some of the best musical artists of this generation, including Tracy Chapman, Erykah Badu, and Jay-Z.

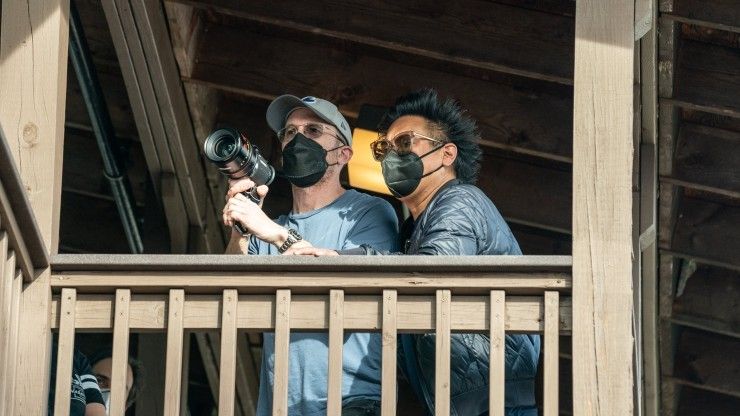

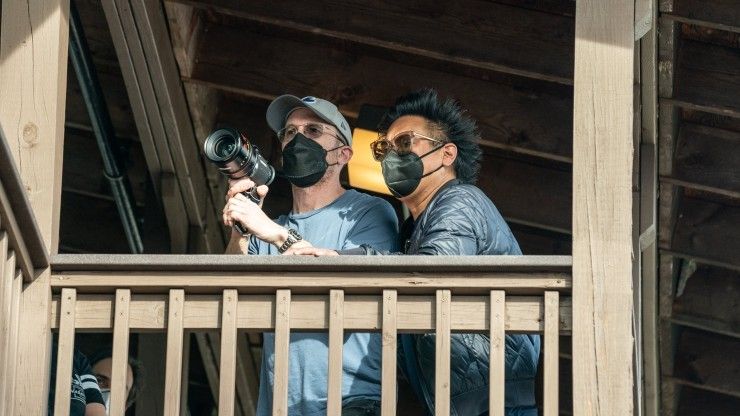

Recently, the cinematographer used Sony VENICE for the first time on The Whale, a heartbreaking and touching story about fatherhood by none other than Darren Aronofsky. Libatique spoke with No Film School about VENICE, how he chooses his kit, and what films built the foundation for his artistic expression.

And there is so much we can learn.

Building Relationships

Before The Whale and even before working with Aronofsky on Protozoa and Pi, Libatique was discovering his own foundation as an artist.

“Before I was really into cinematography, I was sort of introduced to films through friends and Storaro,” he said. Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro is widely recognized as one of the most influential in cinema history, capturing films like The Conformist and Apocalypse Now.

“Bertolucci's The Conformist was a really important one for me because I started to realize that Bertolucci and Storaro had this director-to-cinematographer relationship. They had done The Conformist together, and they did the Last Tango in Paris,” Libatique said. “That sort of inspired me to be a cinematographer, as well as [my outlook on] relationships.”

Even more contemporary work (at least during the 90s), like Do the Right Thing, was a building block.

“That was really influential for me. And again, it was a director-cinematographer relationship that really inspired me with Ernest Dickerson and Spike Lee,” Libatique said.

It’s no wonder that he and Aronofsky then began a storied career that would encompass films like Requiem for a Dream (2000), The Fountain (2006), Black Swan (2010), Noah (2014), Mother!, and now The Whale. Two of which have awarded him an Independent Spirit Award for Best Cinematography.

The Language of Movies

One could argue that if this concept of building and maintaining relationships with his counterparts on set weren’t fundamental to Libatique’s early years as a cinematographer, The Whale would not have come to fruition. And all that came with it, like the lengthy standing ovation for Brendan Fraser.

Based on a play of the same name, The Whale was shot almost entirely in a small two-bedroom apartment, save for a short sequence on a beach. It evokes strong feelings of familial grief and shame, and to capture these emotions, Libatique ventured into a new camera system that he never used before—Sony VENICE.

For Libatique, cameras and lenses “are part of the language that you're baking into the film. Back in the day, it was the film stock and the lenses. Cameras really didn't matter.” But now, in the modern age, cinema cameras play a bigger role. The sensors, the color space, and the sensitivity all take part in making a decision about your film's creative look.

“On The Whale, specifically, I shot Sony VENICE. And that was just due to thinking about what the language was going to be and what my approach was going to be,” Libatique said. “On that film, we wanted to keep it as naturalistic as possible and have as high a sensitivity in the camera so that I didn't have to light so much.”

Without the need for a whole series of lights on set, Libatique and his team allowed the small cast to do what they do best.

“I can keep things away from the actors, and I can allow them to perform. I can give them space to perform, so they didn't have a lot of equipment in their eye line.”

Sony VENICE, with its super sensitive sensor, allows filmmakers to utilize every lumen their lights produce, be they natural sunlight or practical bulbs. In The Whale, the choice of using the VENICE sensor affected the lighting setups, which further affected the performance of the actors.

But that was not all that was different about the tools Libatique used.

“I was just looking for something that I hadn't seen. I hadn't shot a film on the Sony VENICE, and I just needed something kind of in between. I wanted something with a bit of a vibe, but I also didn't want to be too sharp,” Libatique said about the Angenieux Optimo Primes he paired with VENICE.

“There's a nice soft roll-off to them," he said. "And I like the amount of focal lengths that they had. I had never shot them before, and when I tested them from wide open, which I think was T1.9 or T1.8 to T2.8, I really like how they performed."

Paired with the large-format VENICE sensor, the camera kit “allowed me to do exactly what I was aiming to do, which was to light in a very small way and rely on exposure on the lower end of the curve,” Libatique said.

This combination of tools is what Libatique called the “cocktail.”

Mixing the Cocktail

Picking the right tools for the job isn’t just about efficiency or having the most expensive kit on set. It’s about balance.

“You're sort of mixing the cocktail,” Libatique said. “How much of this do I want and how much of that do I want? Once you get into a situation where you pick the camera, you get to LF, say, for example, then you're dealing with large-format lenses, and then you've kind of narrowed your choice. Or if you're shooting [6K] on the Sony VENICE, you've narrowed your choice, so then there's less to choose from.”

While the selection of lenses for large format sensors is quite robust, they are nowhere near close to the number of lenses you get for Super 35 sensors.

“When you're dealing with a Super 35 sensor ... then all the old choices come back into play. And do I want flair? It's become very fashionable to shoot with lenses that aren't quite perfect and sharp because digital is so perfect and sharp.”

For The Whale, Libatique said that other cameras "would've done a fine job, but something about the color space [of Sony VENICE] worked for me and the combination of the lenses. Like I said, a recipe is a recipe, a cocktail's a cocktail. So to me, that’s [how] I think about it. Of course, you could have made the film with another method, but I think this one was the right one, and it works.”

And Libatique says for him there’s no one rule for everything. “Sometimes you want to use a Master Prime, and sometimes you want to use a Kowa, and it really depends on the film.”

Even when budget becomes an issue, there are always options. Libatique said, “luckily, filmmaking has become so democratized" so if a film can't afford an expensive cinema camera, there are more affordable options, like the Sony FX3 of FX6.

Composing for Size

In The Whale, Brendan Fraser (who plays Charlie) donned a very realistic prosthetic to play an obese man who attempts to reconnect with his young daughter. The size difference is quite staggering when you see it on screen.

Capturing this difference in a small frame, like with a Super 35 sensor, could have posed a challenge, especially in the small confines of the apartment set.

For Libatique, picking a sensor is both a “technical and artistic choice. Say, for example, you want a film where you could bring lenses closer to the actor and not have to deal with a very strict minimum focus.”

Like with anamorphics, for example.

“If you want to shoot spherical, but you want to get that focus fall-off that you would get perhaps in anamorphic, then shooting a larger sensor would help you," he said. You have to think of “all the factors that you're trying to achieve with what's going to get me to my goal."

Sony VENICE has a sensor that measures 36mm by 24mm, which allowed Libatique and his team to get up close and personal with the actors on set while still keeping the focus fall-off that they wanted. Having that extra real estate when composing made it easier to set up in the small space of the apartment set and capture the different sizes of actors.

But there were still challenges to overcome.

“The challenge really was how do we get this play on its feet cinematically, and Darren and I just kept working on angles. And he had a great strategy of keeping movement going throughout the characters as sort of rotated around the planet that is Charlie,” Libatique said. “Because our camera was dictated by the movement of the characters, it made our camera have to pan and move and adjust, and it forced cuts to make it kind of interesting.”

When moviegoers see The Whale, they may notice “little subtle chapter divides every time we cut to a wide in the movie.” While there are title cards to denote the days that have passed “within those scenes, all this stuff happens one after another. And in the film, there's sort of language of something like the door knocks, we cut to a wide and all of a sudden another part of that place begins.”

And then they wrapped. Fraser, along with writer Sam Hunter, received their first standing ovation of many. "We just clapped for Brendan and Sam Hunter,” Libatique said. “It was just such an achievement for them, and Darren was so appreciative.”

Beyond all the technical things Libatique covered during our conversation, the most important thing for him was the relationships. Not only with his long-time friend and collaborator Aronofsky, but with Fraser, Hunter, and the entire crew. Production ended where Libatique began, building relationships.

On the Topic of Advice

As we wrapped up our conversation on The Whale, the World Cup, film vs. digital, and what actors should know about the camera, Libatique shared some advice for up-and-coming directors and cinematographers.

Regarding celluloid, Libatique said he was agnostic to the debate but did say that while digital dominates, “I think it would be very sad if [film] was gone. I'm glad there's a presence of film in business and that people are still shooting film because there is a value to it. I don't think that the thing you get in film is a hundred percent replaceable by digital.”

Pivoting to the other side of the camera, Libatique elaborated on veteran actors and his appreciation for what they bring to a production.

“There's a skill level to acting in films that a lot of [actors] have. Understanding peripherally where the camera is the most important. And so a lot of them understand what they look like from one side to another. They see the camera in the periphery, and they adjust, and they know what it takes to make a shot work”

Finally, I asked if there was any advice he was willing to share for cinematographers and directors just starting. While I had imagined the answer would be different for each discipline, I was proved wrong.

Director and cinematographers are both storytellers, Libatique said. "I mean, the most important thing for directors is to be a storyteller.”

Beyond the writing, performance, or even the camera, “I would say don't lose sight of the storytelling just because you want a cool shot.”

Libatique has just finished principal photography on Maestro, the upcoming film about Leonard Bernstein that is written, starring, and directed by Bradley Cooper.

For more information on Sony VENICE, check this article, and if you have some thoughts on Libatique's advice, let us know in the comments!

Your Comment