Anyone who’s ever cut a complex project knows how much they depend on their assistant editors (AEs) to get the job done.

This post was written by Lisa McNamara and originally appeared on Frame.io insider on Nov. 28, 2022.

Navigating through terabytes of footage, managing thousands of elements, and keeping a squadron of departments flying strategically in sync with one another are just a few of the responsibilities that allow the editor to focus on the creative cut. You could almost call the AE the editor’s most trusted wingman.

So when talking about Black Label Media’s Devotion (now in theaters) directed by JD Dillard, it’s fitting that we talked to both the editor and AE.

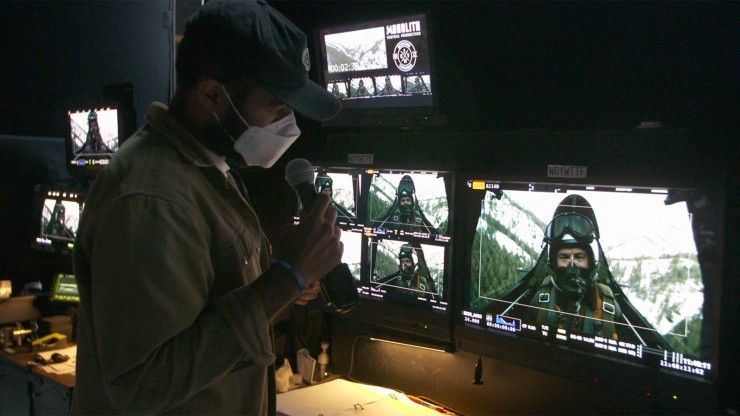

In this installment of Made in Frame, JD took us through his flight plan, while Billy Fox, ACE and assistant editor Russell August Anderson, stepped us through their process using Adobe Premiere Pro and Frame.io to stay on course throughout the production.

You can also check out the extensive four-part interview Morgan Prygrocki conducted with Billy and Russell for the Adobe for Education YouTube channel, below.

A personal mission

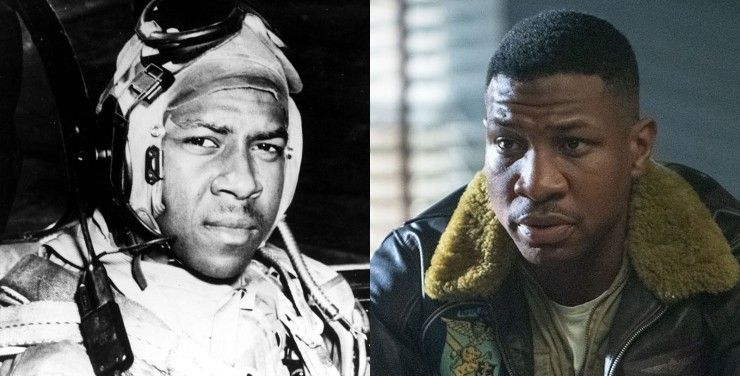

Growing up with a father who was himself a naval aviator, JD was keen to direct Devotion, which is based based on the real-life bond between Jesse Brown, the first Black naval aviator, and his wingman, Tom Hudner, during the Korean War. Beyond his motivation to honor Jesse and Tom’s story, as well as his father’s career, JD felt it was important to assemble a fleet of period-accurate aircraft with the intention of capturing as much footage in camera to replicate the feeling the pilots would have had inside them.

Similarly, when it came to assembling the tools for the project, JD relied on Billy and Russell to devise a workflow that would allow him to have the most hands-on approach possible while working through this ambitious and complex project.

Preparing for take off

Many directors choose editors they have previously worked with and editors, in turn, with assistants they’ve had over the course of many films, but Devotion was the first tour for JD and Billy, as well as for Billy and Russell. In fact, not only had they not previously worked together, they hadn’t met in person until months into the project due to the pandemic. But their connections came through even over Zoom, and thus the team was formed.

As many film editors were learning to retool, working on NLEs was a natural progression for him, and he was able to pursue his passion as he went on to edit numerous films and TV shows including Dolemite is My Name and the Emmy-winning Law & Order. A technology enthusiast, Billy likes to start on a film prior to production to help spec out the tools they’ll need to successfully collaborate with the production team, each other, and the rest of the post team.

Navigating through challenges

Remote workflows were already familiar territory for Billy and Russell. From JD’s perspective, however, there were big challenges associated with having to adhere to Covid safety restrictions. From not being able to sit in the same van during location scouting—a fertile time for discussions and problem solving—to being remote during the first eight weeks of the director’s cut, he was ultimately relieved to realize how far the technology had come and how, in some instances, it would even prove to be advantageous.

Working with DP Erik Messerschmidt (who won the Oscar for Best Cinematography on Mank) JD says, “One thing that Erik and I talked often about was what we could do to see something as close to what the movie is eventually going to feel like—even in the assembly phase. So having our HDR dailies was really helpful to understanding what we were working with.”

Another key advantage to having the HDR dailies available in Frame.io was the ability to compare footage while on set. “You’re shooting a scene and the related portion of that scene was shot a week ago. A lot of that can be done with your video assist, but when you’re shooting the main unit in tandem with the aerial, it doesn’t have all 450 hours of aerial dailies. And some of those things really need to intertwine,” JD says.

“I don’t think we could have done without something like Frame.io. I have never had the feeling of having so much at my fingertips.”

“It was crucial to see the consistency of light or whether a move makes sense if the character’s looking one way and we have a move in the aerials. I don’t think we could have done without something like Frame.io. I have never had the feeling of having so much at my fingertips.”

A solid flight plan

Neither Billy nor Russell are strangers to Premiere Pro. While Hollywood has historically been dominated by other NLEs, more and more productions are actively switching to Premiere Pro for its flexibility, ease of use, and power. Perhaps most notably, David Fincher (with whom Russell also worked on Mank and is currently on his next film) has based his post facility’s pipeline on Premiere Pro for years.

And, like director David Lowery, JD appreciates being able to access his cut and his dailies himself. JD uses Adobe applications like Photoshop and Lightroom on a regular basis and Premiere Pro as a self-described hobbyist. “There were moments in the middle of the night or on a weekend where I just wanted to know if two things go together,” he explains.

“If I wanted to pull five clips and put them in a particular order to see how a certain piece of music felt, I had access to it in a way that I haven’t had before. I felt like I was light on my feet throughout production and my dailies weren’t completely inaccessible.”

LucidLink cloud storage kept their media centralized and Resilio Sync helped them share terabytes of assets with each other. Discord helped Billy by letting him just push a button and easily ask Russell for whatever he needed, which helped them feel as though they were just in the next room instead of in different locations entirely.

All dailies went through Russell, who first organized everything into scenes for Billy. Each reel was then made into its own Project. Billy had his own WIP Project, which is where he could break out from the “God edit” to make changes, and when he was finished he could replace that sequence back into it. Then there were Projects containing things like VFX, music, sound effects, ADR and, most importantly, there was a shuttle Project for sharing sequences. The team used LucidLink to quickly share the Projects back and forth, along with storing paperwork and production documents there.

The music department especially relied on Frame.io. “We’d primarily use it as an inbox/outbox with dated folders and we’d pass elements back and forth. The Transfer app is, in my opinion, as fast as, if not faster than, other competitive services. We’d push a lot of media up there,” Russell says.

And then there was the automation that the Frame.io API enabled. With Russell’s coding background, he was able to save himself from manually organizing the massive quantity of assets. “I wrote some command line scripts, primarily in Python, to automate some of the uploading process, as well as things like batch-renaming large numbers of files and folders. Once files are up on Frame, I learned that they’re essentially just object pointers,” he explains.

“If File A is in Folder A and I copy it to Folder B, File A is not a duplicate, it’s a sort of reference. So moving and copying media is an almost instantaneous process. This is useful particularly in situations with dailies where you need to have the same media organized in different ways —one set of media in folders by production day, another set by scene, another by camera, etc.”

Russell created customized workflows by automating tasks in Premiere Pro, as well. “Some automations seem small and maybe silly, but in the long run they’re really helpful things. Like if you’re sending stuff over to After Effects and you’re doing some quick and dirty offline visual effects work, I had one that you could lasso a bunch of clips and it added 12 frame handles. It sounds like something minor, but as you’re doing this over and over every day it can pile up.”

The Frame.io integration with Premiere Pro also boosted their creative workflow. “During production, the second AE was on location and was dealing with really long string outs of aerial footage,” Russell explains. “She was able to drop in markers to indicate the best parts to check out. She was adding hundreds of markers in Premiere Pro and pushing it to Frame.io, and there would be notes from JD that showed up in the Premiere Pro timeline. That was tremendously helpful.”

In the Creative Cloud

Within Premiere Pro, Billy found the sound tools in Audition to be especially useful. The new AI-powered Remix feature allows you to easily adjust the overall length of your music track, which he found “very impressive.”

They also found Adaptive Tracks to be a powerful tool. This allowed them to route the multi-channel audio to Billy’s 3.0 audio setup (left, right, with center as dialogue) and then feed that into Loopback so the director could monitor accurately through his 2.0 setup.

Russell also worked quite a lot in After Effects, doing things for Billy like stabilizing shots or creating quick comps during production, and relied on the Dynamic Link feature to share them with Billy when he was finished.

Their VFX editor was likewise working in After Effects during production. Billy describes his job as “pretty daunting.”

For his part, JD appreciated all the work the editors were able to do with the tools in Premiere Pro and After Effects. “I think I’ve never had so much opportunity during cutting to get the film as close as possible to what the theatrical experience would be like. Each time we took this film to testing it was simply a Premiere export but because we were able to do our temp visual effects either in Premiere or in After Effects and temp mixing just in Premiere, you realize how broad your limits can be,” he says.

“Because we were able to do our temp visual effects either in Premiere or in After Effects and temp mixing just in Premiere, you realize how broad your limits can be.”

“It ties back to why we wanted to shoot in HDR—it was just how much the in-progress edit can feel theatrical. Given how quickly in the beginning we needed to deliver a cut and move things to VFX, it never felt like there wasn’t something we couldn’t do. That sort of flexibility is great and also a little seductive.”

Up to speed

Devising a workflow of this size is, obviously, a process that has to be well conceived and executed. But once it is, that’s when the creative magic happens.

Billy, whose career includes co-producing and editing Band of Brothers, connected immediately with the script and was all in for this project. It’s one that was dramatically appealing and technically challenging, given the importance of honoring the real people involved and the massive quantity of footage and visual effects.

That’s why it’s extra critical that Billy sets up his timeline in ways that make it most efficient for him to manage both aspects. One of the tricks he employs for maximum flexibility is checkerboarding his picture and his dialogue timelines (explained in the video below), which means that he can adjust edits by easily sliding something on the timeline without having to trim each piece, and turning off the timeline with the old edit.

Another technique he relies on is creating multiple video tracks, so he can easily make alternate versions of a cut. Not only can he quickly give the director options, he can also retain earlier versions on an alternate timeline that he’s simply turned off. How often do directors decide that they want to look at a version that they may have seen months ago? Right. This technique makes it possible for Billy to easily get back to that version without having to hunt for it in previous cuts.

But even with all the technical tips and tricks that time and experience bring to editors like Billy, in his view there’s much more to what it means to be a great editor.

“I believe that the film tells you where to cut,” he says. “If you force an edit, it feels forced. Often someone thinks that if they’re an editor and being paid a salary, they need to make edits. A really good editor knows how to listen to the film and listen emotionally to what you should do or, more importantly, what you shouldn’t do.”

“I believe that the film tells you where to cut. If you force an edit, it feels forced.”

“And then it’s how far that person can reach into their gut. You don’t make edits with your hand or your eyes or brain—you make them with your stomach, which is what makes for the most emotional and powerful storytelling.”

Flying high

It’s clear that Billy believes this with his heart and guts, because bringing JD’s vision to the screen was, in equal parts, making the movie emotionally resonant to a wide audience but also technically authentic to military procedure and protocol in honor of his father and the many people who have served.

In fact, JD recalls how Frame.io even helped bring the movie to his father. “I remember two Thanksgivings ago going to my parents house and I brought up Frame.io on my iPad Air, played it to the television, and showed my dad a scene that I wanted his feedback on. Being able to travel with a movie like that and feeling like it’s safe is now so important to me,” he says.

Billy concludes by saying, “In my career, there are films I’m proud of and some I’m very proud of. Devotion is one I’m very proud of.” He cites one of his favorite scenes, in which Jesse and Tom fly together for the first time. “It’s a beautiful scene,” he says. “It’s a ballet of aviation.”

And in the way that it took a blend of artistry, technology, camaraderie, and reliance on teamwork to make this movie, you could almost call it a ballet of filmmaking that succeeds with flying colors.

Your Comment